What My Call Center Job Taught Me About Free Will

You're not a victim. Chill out.

Hey lovelings! I’ve been meaning to continue my True Power Series, but it was my birthday recently (yay!), and I’ve been finishing up my second album (also yay!), so things got busy here.

So while we wait on the next installment of the series, I’ve got a quick thought to share.

A few months ago I started a temp job at a call center. The job is simple: Healthcare companies contract us to conduct customer satisfaction surveys over the phone. We never ask people for their personal information — just their opinions about the care they’re receiving. I read the questions verbatim off a script, record their answers, and that’s it.

Should be easy, right?

The thing is, it’s almost impossible to persuade anyone to participate in the survey.

For starters, they don’t recognize our number. So naturally, when I introduce myself as calling on behalf of their health plan, they’re suspicious AF (as they should be).

Plus, it’s not a compensated survey. So after I read the part of the introduction that says, “This interview should take about 25 minutes,” I brace myself for the dramatic hang-up sound.

I get it. Who wants to do almost half an hour of unpaid work?

(And why doesn’t the client just pay the respondent to do the survey, instead of paying me to conduct it? I have my conspiracy theories about how they’re actually collecting data about our voices, to train future AI to sound more human over the phone — but I can neither prove or disprove this theory.)

Anyway.

Now that I’ve made maybe tens of thousands of calls, I’ve noticed a fascinating trend in how people respond to unsolicited calls:

They seem to think they’re being victimized somehow.

For example, sometimes I’ll call, introduce myself, and ask if they want to participate in the survey.

Then, with all the indignant rage they can muster, they’ll scream back at me: “IT’S SUNDAY.”

I wait, and then respond with my best Customer Service Politeness: “Would you prefer that we call back on a more convenient day?”

“IT’S SUNDAY,” they repeat again. “Why would you call on the Lord’s Day?!”

If I wasn’t supposed to be polite, I would shoot back, “Why would you answer the phone on the Lord’s Day if it’s soooo holy and sacred to you?”

We have a similar problem on unofficial holidays like Mother’s Day. I can’t tell you how many women were scorned to hear my voice on Mother’s Day. “IT’S MOTHER’S DAY,” they’d whine. “YOU SHOULDN’T BE CALLING ON MY SPECIAL DAY.”

Sometimes this happens on regular days too. We get a lot of “Don’t you know it’s dinner time?!” complaints, as if they can’t simply ignore the call. And I once called a guy who spat back, “I’M WATCHING THE GAME,” as if I was supposed to ~know~ that already, and now I’d rUiNeD his good time!

Do these people not-know that they have the choice to not answer the phone?

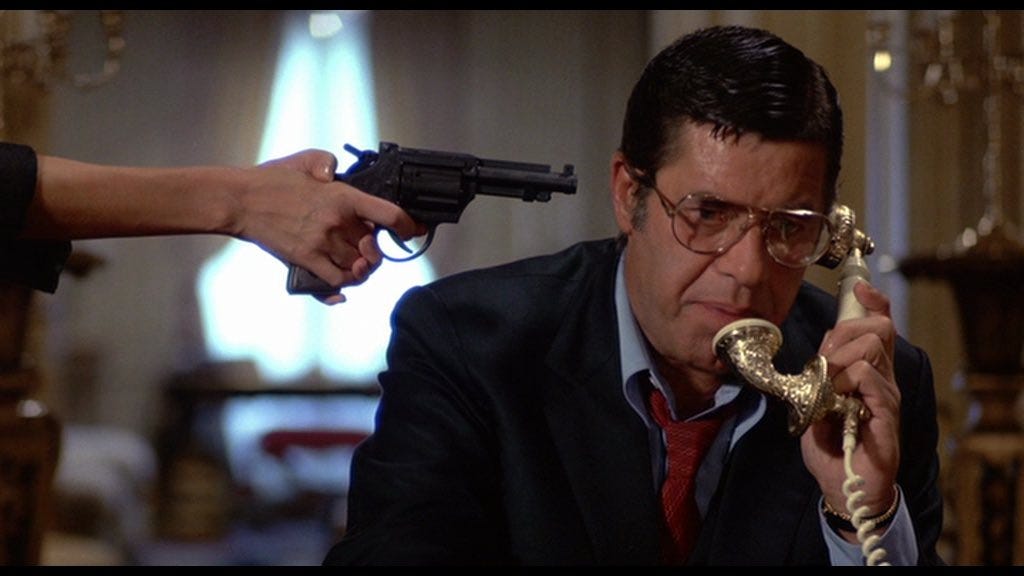

I mean, I’m not exactly holding a gun to their head.

There’s plenty to be said about how our phones have conditioned us to respond to every ring and notification sound, immediately and without thinking. So when someone automatically answers their phone despite not-wanting to, it’s a result of deep psychological conditioning — but the process is so unconscious, that they seem to think I made them do it.

Let’s look at another call center phenomenon:

People constantly lie.

I’m trained to take people very literally. So if I ask someone to participate in the survey, and they respond with, “I can’t, I’m busy right now,” I’m supposed to say, “What day and time works better for you?”

I understand that what they want to say is, “I don’t want to do this survey,”

— but see, that’s not what they actually say.

They say “Not right now” or “I have guests,” or some other indirect, wily substitute for, uh, the actual Truth.

And the problem is, they think this is sufficient communication — so they hang up.

Little do they know that, per my training, I now have to schedule a callback (because they implied that they could do the survey, just at a later time),

meaning I’m going to annoy them again tomorrow…

and the day after that…

and the day after that…

until they figure out that they need to explicitly tell me, “I’m not interested in participating in this survey.”

Then I can stop calling.

Similarly, I am obligated to schedule a callback when someone hangs up without an explanation. Because per my training, theoretically the call might’ve just gotten disconnected — so we’ll try again tomorrow! Again, I can’t assume anything other than what they explicitly tell me.

On the one hand, I sympathize, because I know phone surveys are annoying — and I’m the one conducting them!

But on the other hand, nah, I don’t sympathize, because people should be honest on principle.

It’s actually quite saddening, how people get all weird about these phone calls.

They start stammering and stuttering in response to my questions, as if they’re having a mild panic because — gasp! — a stranger called and asked them a question!

They get annoyed and angry, as if I forced them to answer the phone.

And then they scramble to end the call with excuses and lies, as if the Truth isn’t enough. (Do they think it’s going to hurt my feelings if they just say “I don’t want to”? And why should my hurt feelings stop them from expressing their Truth, anyway? Truth is Truth, whether the person you’re sharing it with likes it or not.)

I get it: Unsolicited phone calls are annoying. I’m not entitled to talk with anyone on the phone. Phone surveys are an archaic method of data collection. I’m not disputing those things.

My point is that, this call center job has illustrated a microcosmic version of the macrocosmic issue, which is a general lack of awareness that we have free will.

In a society of people who gno they’re free and empowered, people wouldn’t feel personally targeted or victimized by phone calls, because they wouldn’t be mindlessly-picking-up-the-phone-just-because-it-rang in the first place…

…nor would they act so wretchedly helpless when that phone call requires them to express themselves truthfully for like, three seconds.

I enjoyed 'this rant' because it's made me feel better about not answering the phone, which I do a lot: eg. if the number shows it's not a number saved, with a name against it, I don't answer it period! If they go on to text me revealing something about themselves which I can identify with I will then choose to reciprocate, or not. You're right; choice is a 'thing' we need to employ more of, thank you and YAH bless <3

I so love and appreciate how you can discern a trend that would fly under the radar for most folks and casually transform it into a valuable moment of contemplation. Thank you! 💕